Friendship in adulthood is rare. Friendship in a foreign land is a lifeline.

At forty-seven, I was a professor in India and a student again in Berkeley. I lived alone, studied hard, and tried to look calm. But loneliness has a way of showing up quietly, usually when you return from a long day and the room is too silent.

About two weeks after I arrived, I was walking back from a heavy epidemiology lecture when I fell into step with three classmates. We began with the usual student talk: the syllabus, the assignments, the fear of exams, and the strange feeling of being back on the bench after years on the dais. By the time we reached the crossing where our paths split, something had already clicked.

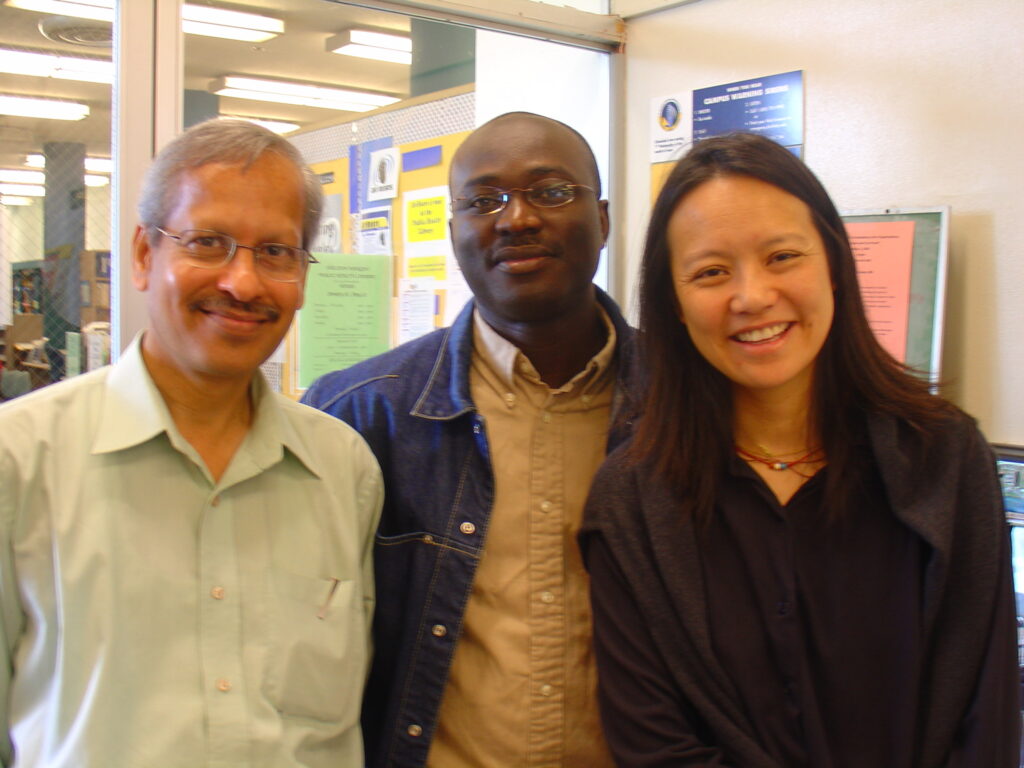

Christine Ho, Maureen Morgan, Joseph Ezoua, and I became a small unit. An unlikely quartet: an Indian doctor, an American woman who was changing direction midstream, a physician-mother from Marin County, and a cheerful health worker from Côte d’Ivoire. We studied together, worried together, laughed together, and slowly began to feel less alone. In Berkeley, they were not just classmates. They were the family I hadn’t planned for.

***

Christine: Quiet Strength

Christine was the gentle intellect of our group. She had studied at Berkeley, gone to medical school at UCSF, and trained in internal medicine. But she wore her achievements lightly, almost as if they belonged to someone else. She was also a mother to Lee and Mika, and she carried that double load with a calm that I still admire.

In class, Christine was sharp. She saw patterns quickly and asked questions that made the rest of us sit up. She had worked at Asian Health Services in Oakland, caring for patients who did not speak English. She had seen the early tremors of SARS even before it became a headline. In 2003, she had travelled to Bihar to work on polio prevention. And when I got stuck in statistics, she became my patient teacher. She would explain again and again, without a trace of impatience, until the fog cleared.

Christine lived in San Anselmo, about twenty miles from my apartment. Visiting her became a small ritual. I would take the BART, cross the Richmond Bridge, and then a bus to her quiet home. The journey felt long, but it always ended with good food, warm conversation, and the comfort of being treated like family.

Our friendship did not end with Berkeley. Christine later worked with the California Department of Public Health and then the CDC. In 2011 she moved to Atlanta. In 2017 she came to India as a TB advisor with CDC, and life brought her back into our orbit in the loveliest way. She visited Sevagram three times. She did not arrive like a dignitary. She came like someone returning to her own people.

My granddaughter Diti took to her instantly. They spoke about books, exchanged reading recommendations, and treated each other like old friends. During Christine’s visit in May 2019, I noticed she was wearing a white and turquoise kurta. It was the same one Bhavana had gifted her in Berkeley in 2004. Years later, in January 2023, Christine visited again. As she left for Nagpur airport, she messaged me: “Hi SP… I just looked in the bag and saw that Bhavana gave me a beautiful dark blue silk shirt! It is really beautiful and she really should not have. I still remember the white and turquoise kurta she brought to Berkeley for me. Really so thoughtful.”

Some friendships do not fade. They simply travel.

***

Joseph: The Big Brother

Joseph Ezoua was the heart of our group. He came from Côte d’Ivoire, and he brought with him the warmth of West Africa. He would tell us about his country, the music, the rainforests, the beaches, and the kind of life that feels colourful even in memory.

Joseph also carried a burden we did not. His first language was French. His English was good enough for daily life, but Berkeley was not daily life. It was fast, technical, and unforgiving. He had to work twice as hard just to keep pace. He never complained. We helped him with language and phrasing, and he repaid us with laughter and morale. When Joseph was around, the room felt lighter.

When Bhavana visited me in December 2004, we had a small welcome party in my apartment. Joseph arrived with gifts from his country, including a beautiful frame that we still have. At one point, he turned serious, pointed to himself, and told Bhavana, “Bhavana, I am your big brother now. If anyone here hurts you, you come to me.”

He said it with a smile, but the feeling behind it was real. In a place far from her own brothers, Joseph offered her the protection of family.

Joseph eventually returned home and later worked with UNDP in Côte d’Ivoire. But to us, he remains the big brother who stood guard in Berkeley.

***

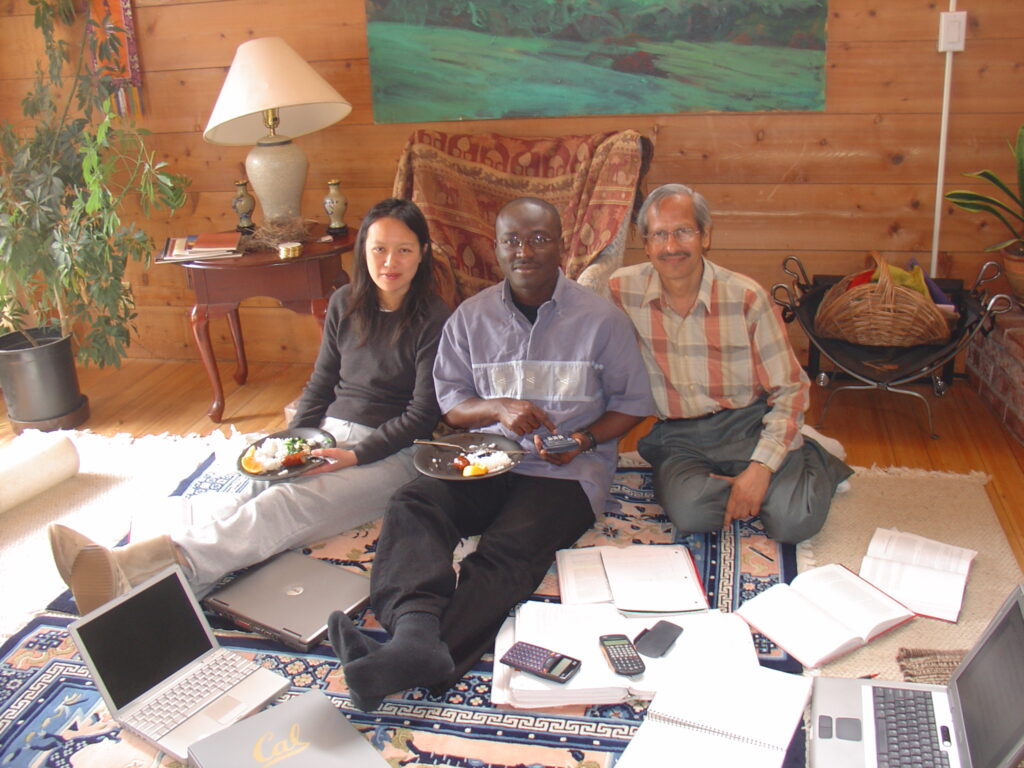

Maureen: My Compass

Maureen Morgan became my guide to American life. She was local to the Bay Area, and she understood things I was still trying to decode. She became my study buddy. Many evenings were spent at my place, going over assignments, making sense of readings, and trying not to panic.

Maureen also showed me the real Berkeley. She introduced me to the Farmers’ Market and the idea of organic food. I had grown up respecting farmers, but this was a different kind of admiration: for people who grew food while trying to protect the soil and the future.

When Bhavana came to Berkeley in December, it was Maureen who drove me to the San Francisco airport to pick her up. She did not just come as a driver. She came with roses and a box of homemade cakes. That was Maureen: practical, thoughtful, and quietly generous.

Driving in San Francisco frightened Bhavana and me. The roads climbed like walls. At every steep turn, we held the door handle as if it could save our lives. Maureen would laugh and drive on, as if gravity had signed a peace treaty with her.

When Bhavana left a month later, I was low. Maureen drove us to the airport again. After the goodbye, she did not drop me back to an empty room. She took me out for dinner, talked to me, and made sure I ate something. She knew what silence can do to a person.

Over the years, I watched Maureen’s journey with pride. She went from being an Emergency Room Technician to becoming a physician. She trained, specialised, and eventually became a gastroenterologist in Richmond, California.

Before I left Berkeley, we spoke about books. I mentioned I wanted to read The Tennis Partners by Abraham Verghese. On my last day, Maureen handed me a gift-wrapped package. It was the book. She had remembered. Inside was a card with words I still keep close: “Your name fits you exquisitely well, for you have a brilliant light shining from deep within… I can only imagine what a tremendous amount of courage it took to leave India… to come and study at UC Berkeley… I consider you part of my family, and I will miss you terribly.”

How do you not carry a line like that for life?

***

The Feast That Sealed Us

The most joyful part of our friendship was the exchange that happened over food. When Bhavana visited, she decided to cook for my Berkeley family. Our small apartment on Channing Way became a miniature banquet hall.

She made a proper Indian meal: curries, rice, and desserts like shrikhand and kheer. I still remember Joseph, Maureen, and Christine sitting in my studio, unsure at first what to do with so much food and so much spice. Then they followed our lead and began eating with their hands. They did not stop. They asked for seconds. They licked their fingers without shame. The next day, they told anyone who would listen that Bhavana was the best cook they had ever met.

Bhavana smiled when she heard that. I think she felt, for the first time in weeks, that Berkeley had become kinder.

***

What Berkeley Really Taught Me

Looking back, I realise the MPH degree was only half of what I gained that year. The other half was simpler, and perhaps more important.

Kindness travels. Friendship crosses borders. And if you keep your heart open, even a foreign city can begin to feel like home.