The climax of any Master’s program is the thesis. For me, it was more than an academic requirement. It was the moment the rubber met the road. After months of theory, I had to apply it.

I worked with Madhu Pai, Lee Riley, and Art Reingold on a systematic review and meta-analysis. We chose a topic that mattered deeply to India: how accurate bacteriophage tests were in diagnosing tuberculosis.

As a clinician, I was used to things I could see and touch, a patient’s breathlessness, a murmur, a swollen ankle. Research felt different. It lived on paper, inside tables, behind confidence intervals. Madhu taught me that good research is not magic. It is discipline. He pushed me through the hard work of data extraction. We read hundreds of papers, separated the good from the sloppy, and entered numbers into large sheets, one study at a time. Every digit was checked and rechecked.

He introduced me to Stata and EndNote. To me, they felt like a new set of instruments. But more than the software, I learned something that stayed with me: respect for data. You don’t twist numbers to say what you want. You listen carefully, even when the answer is inconvenient.

Even today, I still have those old yellow data sheets. They remind me of the year I stopped being only a reader of medical literature and became, in a small way, a creator of it.

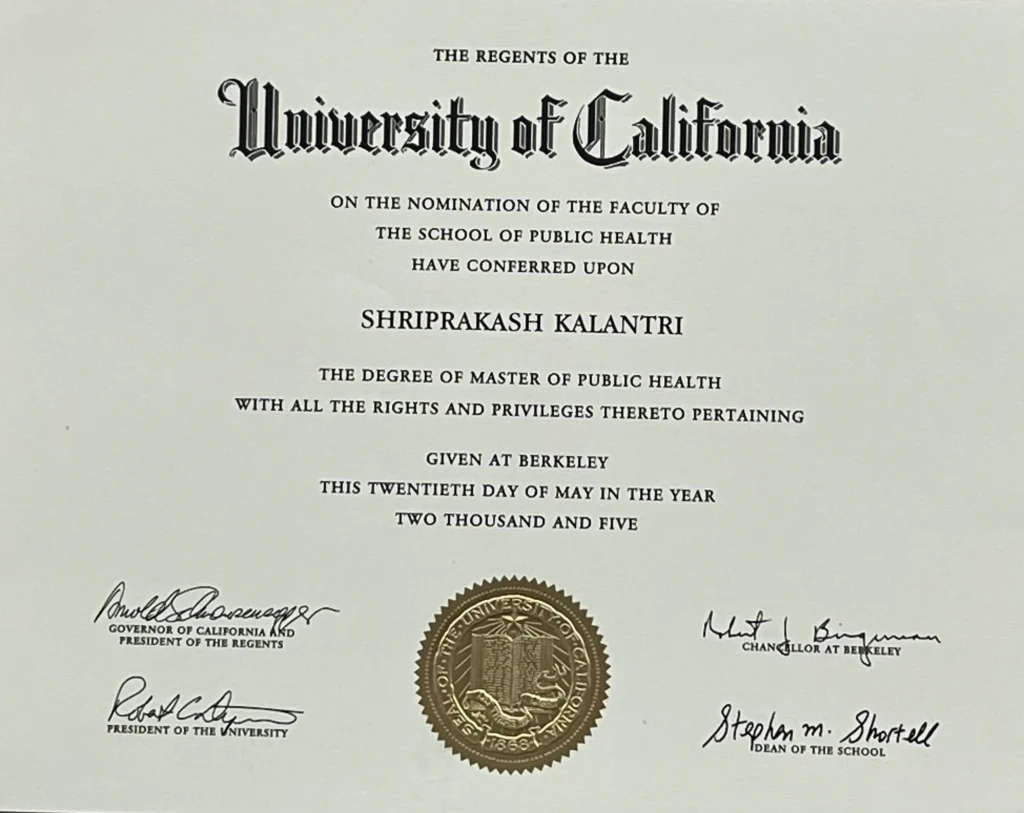

The work paid off. I defended my thesis before Art Reingold and Allan Smith. And before I had even packed my bags, our paper was accepted: Bacteriophage-based tests for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical specimens. For me, it felt like a certificate with weight.

***

Paul Farmer and the $30 Gown

On May 17, 2005, the sun shone brightly over the Berkeley campus. Graduation day. We rented golden gowns for thirty dollars.

When I pulled the heavy cloth over my shoulders and adjusted the cap, I felt a surge of emotion I had not expected. I was in my mid-forties, a professor back home, yet standing in a line of twenty-somethings, I felt a boyish pride. That gown was not just ceremony. It was proof. I had stepped out of my comfort zone, survived a demanding year, and earned a new identity: student again.

The School of Public Health had invited Dr. Paul Farmer to give the commencement address. Farmer was already a legend. He had worked among the poorest in Haiti, Rwanda, and Peru. He did not only treat disease. He fought the injustice that produced it.

He spoke without drama, but every sentence landed. One line stayed with me: “Passion and indignation have a place in public health.” In a world of numbers and models, he reminded us that behind every statistic there is a human life.

Paul Farmer died suddenly in February 2022. But on that day in 2005, he made us feel that public health could be both science and conscience.

***

The Lunch Disaster

After the ceremony, I hosted lunch at my apartment. Bhavana had returned to India by then, so I was on my own. I ordered vegetarian Indian food from Vick’s Chaat.

My calculations were based on Indian habits. I assumed people would eat politely. I was wrong.

The moment the boxes opened, the smell of samosas and curry filled the room. My guests included professors, classmates, and friends who had become family. And the Americans, it turned out, loved Indian food with a seriousness I had not predicted. Within minutes, the trays were scraped clean. People were still looking for seconds. I stood there, embarrassed, amused, and oddly happy.

It was a classic desi planning error. But it became a memory I still smile at.

***

The Visa Cliffhanger

A week before my flight back, I discovered something that made my stomach drop. I needed a transit visa for London Heathrow.

By then I had vacated my apartment. I had sold my furniture. I was living out of a suitcase. The British Consulate required me to send my passport to Los Angeles by post. They promised a five-day turnaround. I had six days.

I mailed it and spent the next week checking the mailbox like a man waiting for a lab report that could change his life. Without the passport, I was stuck. Homeless in Berkeley, unable to fly, trapped in paperwork.

On the sixth day, less than twenty-four hours before my flight, a courier envelope arrived. I tore it open. The passport was inside, visa stamped.

Only then did I breathe properly.

***

The Farewell Letter

In the last quiet days, sitting in my empty apartment, I felt I could not leave without saying goodbye. I wrote an email to my friends and colleagues.

Dear Friends,

It was the best of times; it was not the worst of times. I’m about to finish my time in Berkeley soon! A year at Berkeley—educating, entertaining, exciting, and at times exasperating—would come to an end!

When I arrived in Berkeley last fall, I was in my mid-forties and struggling with mid-career blues. I knew I had some gaps in my knowledge… So, I decided to come to Berkeley to learn more. But, I’m usually a shy and introverted person… The idea of being in a foreign land and living on my own for a year without knowing how to cook was a bit overwhelming.

Despite the initial challenges, I managed to adapt and thrive… I learned how to become self-sufficient and even managed to make perfectly round rotis – a significant accomplishment for me! What did I learn in Berkeley? I learned the fundamentals of statistics, epidemiology, and evidence-based medicine… But most importantly, I learned that to find answers, one must ask the right questions.

I won’t fall into the familiar trap of comparing the US with India. Berkeley has filled my heart with a sense of achievement and fulfillment. I loved Berkeley, and my eyes may tear up when I say goodbye.

***

The Return to Reality

The flight back was long, across time zones and moods.

Somewhere over the Atlantic, I read an email from my friend Dr. MVR Reddy in Sevagram. It pulled me back to earth. He wrote about the usual chaos: inspections, entrance exams, confusion over admissions. He even wrote about Amrita’s future schooling and said, gently, that after what I had seen in America, I might have a different perspective.

He was right.

I was returning to the same Sevagram, with its heat, its constraints, and its daily pressures. But I was not returning as the same man. I was coming back with tools: Stata for my data, epidemiology for my questions, and Paul Farmer’s words sitting quietly in my conscience.

The Berkeley year had ended.

The mid-career blues had not just lifted. They had disappeared.

I was ready to go home.