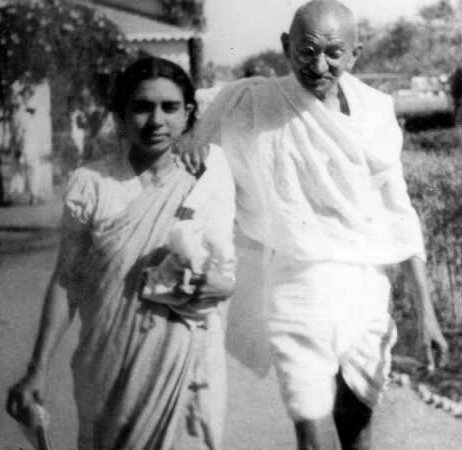

Although I joined MGIMS in the summer of 1982 and Dr. Sushila Nayar remained the Director until her death in January 2001, our paths rarely crossed in any formal sense. For those two decades, I had almost no interaction with her. I do not recall ever meeting her face-to-face in her office. To the world, she was a colossus: Mahatma Gandhi’s personal physician, a freedom fighter, a former Union Health Minister, and the builder of institutions. To us in Sevagram, she was “Badi Behenji”—a name that carried affection, reverence, and a quiet warning.

She was the institution’s conscience and its compass. She had a rare presence that did not require a microphone; she could walk into a ward and make everyone straighten their backs without saying a syllable. She was fiercely pro-poor, allergic to pretense, and possessed a famous, purposeful temper that she used like a surgical instrument against laziness. Many of us found her difficult in our younger years, but we eventually realized she was difficult for the same reason a good teacher is: she refused to let us remain mediocre.

***

The Rituals of Prena Kutir

My limited personal interactions with her occurred only in the final decade of her life, when her heart began to falter. Dr. A.P. Jain, her physician, looked after her with a devotion that saw him visiting her residence, Prena Kutir, every single day for ten years. Prena Kutir was a small, modest, one-bedroom dwelling—frugal and austere, reflecting the Gandhian simplicity she lived by. Day after day, year after year, Dr. Jain would go there to record her blood pressure and exchange pleasantries. Whenever he was on leave, he would ask me to cover for him.

I might have gone no more than a dozen times. Even as a faculty member, I was shy and in awe of her, hardly daring to speak. By contrast, she was an unnervingly warm host. She would welcome me as “Doctor Saab,” despite being four decades my senior. She would generously extend her arm for the sphygmomanometer—those were the days before digital instruments—and keep her eyes fixed on the rising mercury column. Then, with a polite smile, she would ask, “Theek Hai?” (Is it okay?)

If I told her the reading was high, she would laugh heartily and offer a human excuse: “I didn’t sleep well,” or “I am constipated,” or jokingly, “These days, even the blood pressure does not listen to me!”

***

Butter, Mangoes, and Motherly Love

As a perfect host, she would insist I sit. She would take slices of bread, smear them with butter, sprinkle them with salt, and command me to eat. “Don’t look at the butter,” she would say, “and don’t be afraid of heart disease!” During the summers, she would slice fresh mangoes and arrange them on a plate with motherly care.

When it was time to leave, she would insist on escorting me to the door, regardless of my protests. She would stand there, thanking me profusely, and wait until I had kicked my scooter to life and sped past her residence. In those moments, I never saw the administrator, the former Member of Parliament, or the woman who had stood beside Gandhi from the late 1930s until his end. I only saw a woman of immense kindness.

***

The Unwritten History

In her later years, I began writing “Sevagram Stories,” attempting to chronicle how MGIMS was conceived and how Behenji had drawn the best minds from Delhi, Chandigarh, and Nagpur to this rural outpost. To my frustration, there was no written record of this history. I had to rely on the fading memories of the elders still among us: Mr. P.L. Tapdiya, the current President who had been here since 1968; teachers like the Narangs, Dr. O.P. Gupta, A.P. Jain, Karunakar Trivedi, Dr. Ingely, Dr. Chhabra and Dr. Ulhas Jajoo.

Behenji had compiled the unfinished work of her brother, Pyarelal, on Gandhi’s biography, but she never dictated her own memoirs. A few months ago, I met Prabha Desikan (MGIMS Class of 1984) and lamented this void. I told her how much I wished I had gone to Behenji and requested her to tell me the stories while I sat at her feet and documented them. I never did, for two reasons: the thought never occurred to me then, and even if it had, I was too introverted—too afraid of her aura.

I watched other professors go daily for tea, to play cards, or to recite the Hanuman Chalisa or Sundar Kand with her. I never did that. Today, I wish I had shed my inhibitions and possessed that “Punjabi boldness.” I should have looked her in the eye and, like a journalist, extracted those pearls of history. I blame myself for that silence.

***

The Wedding Card and the Orderly

There is one memory that still stings—a testament to my own social awkwardness. In February 1984, I got married. I desperately wanted to invite Behenji to the reception at Jaishree Bhavan, but I couldn’t muster the courage to face her. I walked to her doorstep once or twice and retreated. Finally, I committed a grave social blunder: I asked the Medicine OPD attendant, Ramu Chavan, to hand her the invitation card.

For a woman of her stature—a Punjabi, a politician, and the head of the institute—to receive a wedding card from a faculty member via a hospital orderly was unthinkable. Predictably, she did not attend, nor did she write a letter. After the wedding, I failed to take my wife, Bhavana, to seek her blessings—a routine campus tradition. My shyness must have appeared to her as the rudeness of a mannerless lecturer who lacked social grace. I could not help it then; I can only regret it now.

***

The Full Circle

The clock turned full circle in 2001. Six months after she passed away, Mr. Dhirubhai Mehta asked me to compile and edit a commemorative book on her: Bapu ki Beti, Hamari Beti. I spent days and nights with Prabha Desikan, collecting old photographs and inviting people to write their tributes.

This was my delayed homage. It was the respect I should have paid her while she was still with us. When she died, Sevagram felt as if it had lost its protective roof. The OPDs continued and the ward rounds happened, but a certain gravity disappeared. We realized then that the hospital could no longer rely on one towering personality to keep it aligned.

Modern administrators love their charts and their “systems.” Behenji had no use for them. Her system was a mixture of Gandhian discipline and a fierce, often terrifying, personal loyalty to the poor. She wasn’t an “administrator” in the corporate sense; she was a guardian. And like any guardian of a large, unruly family, she kept us in line not through files, but through the sheer impossibility of saying ‘no’ to her.