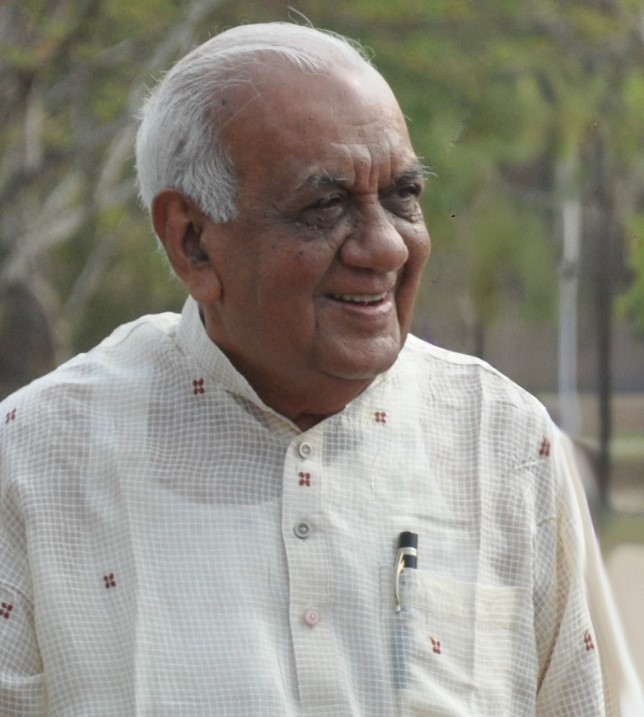

After the iron discipline of Dr. Sushila Nayar came the warm, chaotic heartbeat of Mr. Dhirubhai Mehta. If Behenji was the soul of MGIMS—severe, principled, and formidable—Dhirubhai was its life force. A Chartered Accountant by training, he understood finance the way a tabla player understands rhythm: not by calculation alone, but by a deep, percussive instinct. He walked away from the high-stakes corporate corridors of Bajaj Auto and stepped into the dust of Sevagram, trading Mumbai’s polish for the daily, unglamorous mess of a rural hospital. He brought with him a Mumbaikar’s quick wit, a Gujarati’s unapologetic love for food, and an administrator’s rarest gift—the ability to trust a person’s character before trusting their paperwork.

When he first arrived in 1982, he never bothered with the stiff stereotype of a hospital president. He would laugh at his own lack of medical vocabulary, joking that he couldn’t spell half the departments he was supposed to run. Yet he possessed a Nehruvian eye for talent; he drew academic giants like Manu Kothari, Ashok Vaidya, B. S. Chaubey, and G. M. Taori into our orbit, lending intellectual weight to an institution that city-dwellers often dismissed as peripheral.

***

Tea at Six and Decisions by Seven

Our relationship did not begin in a boardroom or across a mahogany desk. It began in my home in Vivekanand Colony at six in the morning. He would walk in unannounced and unpretentious, asking after Bhavana and the children before moving seamlessly into hospital matters as if the two belonged to the same breath. To Dhirubhai, the institute was not a “system” to be managed, but a family enterprise to be nurtured.

He possessed a profound distrust for thick files and an almost mystical reliance on gut feelings. “Don’t confuse me with data,” he would say, a mischievous glint in his eye as he waved away a bundle of statistics. “I’ve already made up my mind.” It wasn’t that he lacked rigor; it was that he believed hesitation in a hospital was a form of cruelty. He preferred to make a decision at speed, own it fully, and deal with the consequences later. It was this very instinct that shaped my own career, for it was under his watch that I became the “Reluctant Medical Superintendent.” He found my total lack of ambition an amusing oddity in a world where titles are chased with the fervor of religious pilgrims.

***

The 7 O’Clock Darbar

Dhirubhai’s true genius was his accessibility. Every evening, his office transformed into what we called the “7 O’clock Darbar.” It was a daily open court where the hierarchy of the hospital dissolved. Anyone could walk in: a senior surgeon, a junior resident, a clerk from accounts, or a ward attendant. Ideas, complaints, and gossip flowed in a single stream, and quite often, solutions emerged with stunning speed.

A single phone call from that room could unlock fifty lakhs for a new ICU or a palliative care ward. He did not always demand elaborate proposals; he gambled on men rather than systems. While that trust carried risks, the results were visible in the brick and mortar of an expanding MGIMS. Under his leadership, we took ethical stands that were inconvenient and unpopular—unlinking academic activities from pharmaceutical sponsorship and banning medical representatives from campus. He pushed us into the malnourished heartland of Melghat, visiting remote centers not for a photograph, but to remind us, and perhaps himself, why Sevagram existed.

***

The “I” Specialist and the Dhokla Diplomacy

Dhirubhai was never a saint carved in marble. He was wonderfully, maddeningly human. He had a predictable weakness for flattery and suffered from what we affectionately called the “I, Me, and Myself Syndrome.” We joked that he was an “I Specialist” because of his penchant for name-dropping ministers and governors as if he were reciting a grocery list. He enjoyed being the sun around which the room orbited.

His love for food was equally legendary. Faculty members learned quickly that the most efficient route to a new grant ran through a home-cooked Gujarati breakfast. He could discuss a multi-crore budget with a straight face while keeping a predatory eye on the last piece of dhokla. Yet, beneath the showmanship was a deep sincerity; he wasn’t performing kindness, he was living it.

***

The Slow Fading and the Last Call

Time, however, eventually begins to edit the most vibrant of men. As the years passed, the sharp accountant’s mind began to soften. His memory faltered, and the decisiveness that once defined him became a wandering narrative. He would sit for long hours in his office, drifting into anecdotes, unable to reach the conclusions that once came in a heartbeat. It was a painful transformation to witness—not because he was weak, but because he was a builder who could not bear to step away from what he had built.

Every day in Sevagram, he would stand before the idol of Goddess Durga for fifteen minutes, head bowed in unhurried surrender. “I owe everything to Amba Mata,” he would say. It was a startling contrast—the man who commanded destiny in the boardroom bowing like a child in the temple. He knew that institutions survive on grace as much as they do on intelligence.

On April 22, 2022, Dhirubhai passed away at Bombay Hospital. Even on his deathbed, surrounded by city specialists, he bypassed them all to call me. “Is the treatment right?” he whispered. It was the quintessential Dhirubhai question—half anxious, half practical, and entirely human. When the news reached Sevagram, the sky felt a little lower. I had not just lost a President; I had lost a father figure who taught me that sometimes, you don’t need a file to make a decision. You only need a heart, a gut feeling—and a good cup of tea.