A Leap Across Wardha

By the eighth standard, Craddock High School had become a second skin. The classrooms, the playground, the familiar faces — together they formed a small, reassuring world. I was comfortable there. That was precisely the problem.

I could see, dimly but unmistakably, that the road ahead would demand a command over English and science that Craddock could not give me. Not because the school was poor — it was not. But it was teaching me in Marathi, and I had begun to sense that the world I wanted to enter would not wait for translation.

If I stayed, I would remain safe. I would also remain limited.

———

The Friends I Would Leave

What made the decision harder were the friendships I would have to abandon. My days at Craddock were built around people: Suhas Jajoo, Chandrakumar Fattepuria, Chandrashekhar Amte, Narendra Gharpure, Avinash Bhagwat, Kiran Chawade, Vijay Ashtankar, Ravindra Chawade, Namdev Vaidya, Dipak Kalode, Anil Fadnavis, Vishweshwar Mohnapure, and Charudatta Shirpurkar. Among the girls: Asha Fulambarkar, Bharti Deshpande, Lalita Pendsey, Sushma Mondhe, and Mira Pendsey.

Their names were woven into the ordinary fabric of my days — shared lunches, whispered jokes, the easy companionship of adolescence. To leave Craddock was, in a sense, to leave all of them.

Only two came with me to Swavalambi Vidyalaya: Shekhar Deshkar and Sunil Helwatkar. Two doctors in Wardha — Dr. M.K. Pawar and Dr. C.W. Warhadpande — also moved their children, Sunil and Vasanti respectively, to the same school around that time. But the rest stayed behind.

—

A note on the names: a reader might wonder how a man of sixty-nine recalls them with such precision. The answer is not elephantine memory. My friend Laxminarayan Sonwane — Babya to those who know him, a twist from Baban — gave me a copy of an old Craddock register that carried the names of students from those years. A WhatsApp group of former Craddock friends filled in the rest.

Memory is rarely individual. It survives in groups.

———

The School Across Town

Six years before I arrived, in 1963, Swavalambi Vidyalaya had taken a bold and unusual step: it began teaching science in English. In a town like Wardha, this was not a small decision. It was a declaration.

At thirteen, I understood none of this consciously. I only knew, instinctively, that this was where my future lay.

On 4 June 1969, I joined its sixth batch. I did so quietly, without discussion, and without seeking my parents’ permission. It was not courage. It was conviction — which is a quieter thing and, in the end, more reliable.

Six weeks later, Neil Armstrong would step onto the moon. I knew nothing of destiny or metaphor at the time. I only knew that I had crossed the town of Wardha to enter a new school. Yet, in its own modest way, that crossing marked the beginning of everything that followed.

———

I walked through the big gate of Swavalambi with my eyes forward. To the right stood the Headmaster’s office — a room of great quiet and respect. The Biology section opened onto a sprawling, sun-drenched courtyard. The school smelled of possibility, which is a smell you recognise only in retrospect. I did not look back at Craddock. There was nothing to be gained by it.

***

Of Masters and Mitigated Math

The Headmaster was Mr. Parshuram Bhajekar. It was a delightful irony that a man named after the fiery, axe-wielding legend of Hindu mythology was, in reality, the most mild-mannered and soft-spoken of souls.

In the ninth grade, I reached a crossroads: Mathematics or Biology. I found the former to be a thorny, unyielding thicket of logic that I simply did not enjoy. I approached Mr. Bhajekar with my desire to switch. He listened with a curious, scholarly patience, and after hearing my plea, he granted me passage into the world of living things. It was a risky choice, perhaps, but that day, standing alone in the corridor, I felt the immense, quiet relief of a boy who had finally chosen his own path.

My school leaving certificate preserves the dates—June 4, 1969, to April 30, 1972—but my memory holds the atmosphere. I remember the scorching May of 1969, oscillating between my old life and the new, just after my elder brother’s wedding. On that first day, I was a stranger among forty-five students. Only four were girls—Kishori Ghirnikar and Rekha Sapkal, who would both go on to join me in the medical profession, and Vasanti Waradpande.

The boys formed a sprawling tribe: Avinash Joshi, Baba Chutke, Bansod, Brijmohan Rathi, Dilip Joshi, Deshpande, Jabbar Khan, Kaushal Mishra, Kuldhariya, Mohan Dubewar, Pandey, Rajendra Phadke, Ravindra Vaidya, Shekhar Deshkar, Sunil Farsole, Sunil Helwatkar, Sunil Pandit, Suresh Singhania, Swarn Singh, Vijay Pawar, Vinod Adalakhiya, Virulkar, and Yeole. We lost Sunil Pawar to throat cancer in 2022, but I still see him clearly at the school’s 25th-anniversary science fair. He was a master of his craft, single-handedly constructing an electric heater on a small brick while I stood by, a mere observer who nevertheless basked in the reflected glory of the prize he won.

***

The Khadi Cap and the 10-Paise Prayer

Education was a modest expense then; tuition was Rs 7.20 per month. However, because my brother was studying commerce in the same halls, I was granted a “brother’s concession.” My parents paid a mere Rs 3.60—exactly the fare for a third-class train ticket from Wardha to Nagpur.

Our mornings began with a prayer by the poet Ramnaresh Tripathi. But the true ritual of the morning involved the white khadi cap. It was mandatory, a symbol of our school’s heritage that we viewed with a mixture of reverence and deep teenage embarrassment. Students from other schools, liberated from such headgear, would mock us. Consequently, we developed a strategic habit: the cap remained stuffed in our pockets until we reached the very threshold of the school gate, at which point it was perched upon our heads with a resigned sense of duty.

That prayer stayed with me for fifty years. Decades later, when my friend Dr. V.K. Gupta visited from Lucknow and gifted me Harivanshray Bachchan’s autobiography, I found a startling echo of my childhood. On page 125, Bachchan writes of reciting that very same prayer at the Mohtashim Ganj Municipal School in Allahabad in 1915. Five decades and a thousand miles could not dim the resonance of those words.

शीघ्र सारे दुर्गुणों को, दूर हमसे कीजिए।

लीजिए हमको शरण में, हम सदाचारी बनें,

ब्रह्मचारी धर्म-रक्षक, वीर व्रत धारी बनें।

॥ हे प्रभु आनंद-दाता, ज्ञान हमको दीजिए…॥

***

The Hitler Diversion and the Botany Models

We were guided by a dedicated assembly of masters. Mr. Ramkrishna Pande and Rajendra Singh Thakur oversaw our English; Mr. Shambhusharan Gupta taught Hindi; and Mr. Chintaman Hetre handled Marathi. In the sciences, we had Mr. C.D. Zamvar for Botany, M.J. Gandhi for Zoology, and Mr. Vinayak Zope for Physics. Chemistry was a shared labor between Messrs. Rayalkar, Band, Dattatraya Chitale, and Chaudhary, while Mr. Ambulkar marshaled us for PT.

Mr. Ramkrishna Pande, though our English teacher, possessed a heart that beat for History. We students, ever-opportunistic, discovered that a well-timed question about World War II or Hitler’s tactics would derail the entire lesson. Mr. Pande would forget the English grammar on the board, sit cross-legged on his desk in his dhoti, and lose himself in the ruins of 1940s Europe. By the time the bell rang, he would realize with a start that the German army had advanced, but our English had remained precisely where it started.

Then there was Mr. Chitrakumar Zamvar, a young man in his mid-twenties who brought the microscopic world to life. With models ranging from the humble amoeba to the malarial parasite, he bridged the gap between the textbook and the eye. Even when he was replaced by Mr. Madanlal Tiwari, the fascination remained.

***

The Library and the Drawing Exam

I was a creature of the library. I spent my afternoons at the Rashtra Bhasha Pustakalaya on the Bajaj Electricals campus, where Mr. Purohit would suggest new worlds to explore. I devoured the giants of Hindi literature—Munshi Premchand, Jaishankar Prasad, Mahadevi Verma, and Acharya Chatursen—and eventually the modern prose of Mohan Rakesh and Manu Bhandari.

I even harbored artistic ambitions. In 1969, I sat for the Government Drawing Exam. I was famous among family and friends for my chalk portraits of Shivaji Maharaj and Lord Ram, but the government examiners were less impressed than my aunts; they awarded me a “C” grade.

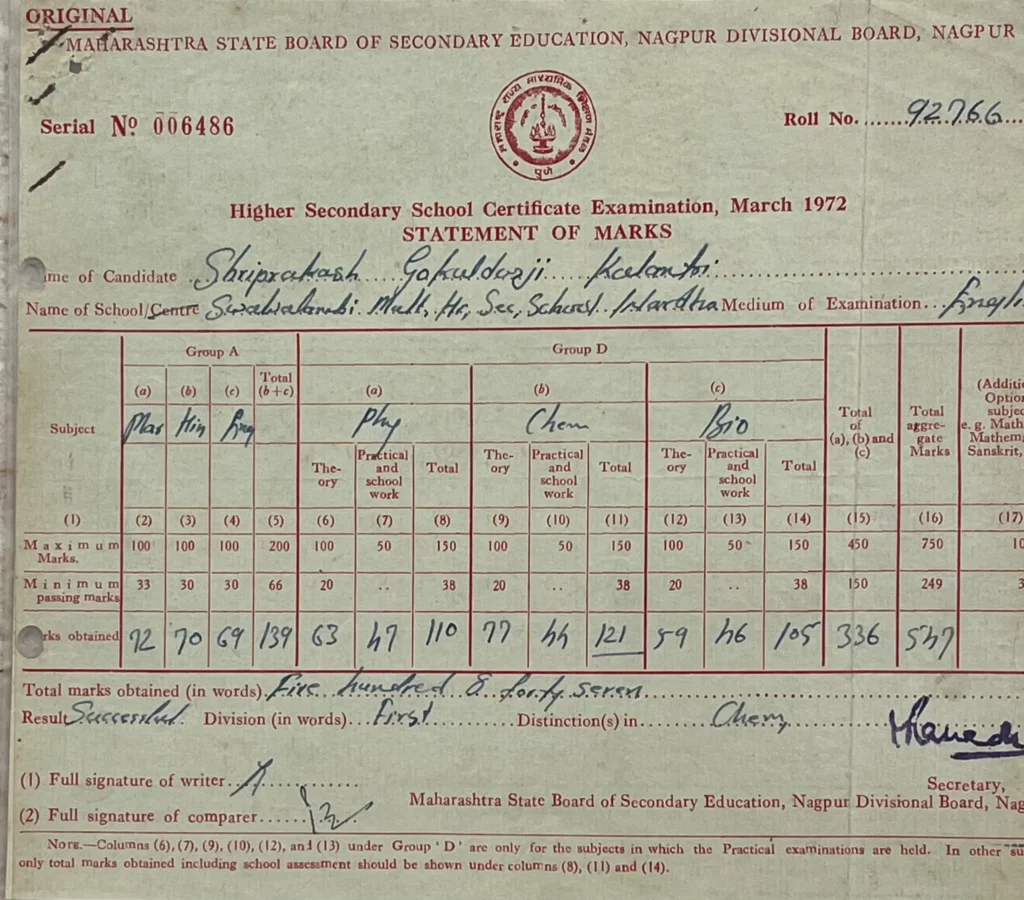

By the summer of 1972, the Board exams arrived. I found my stride, earning a distinction in Chemistry and solid marks across the board: 72 in Marathi, 70 in Hindi, and 69 in English. My confidence was buoyed, though I still hadn’t fully grasped that these numbers were the keys to a medical life.

***

The Miracle of the Machine

In 1970, when I was in the eighth grade, the domestic peace of our home was shattered by my mother’s illness. At forty-five, she was besieged by the “shadows” of menopause—hot flashes, palpitations, and sleepless nights. Our local physician, Dr. Warhadpande, was stumped.

My father’s concern grew into a quiet desperation until Dr. B.C. Chandak, an intern in Nagpur, arranged for a visit from the renowned Dr. K.L. Jain. The arrival of a Nagpur physician in Wardha was an event of local significance, but what followed was legendary.

Dr. Jain arrived with a bedside ECG machine—a rare, mystical device in those days. As he recorded the electrical signature of my mother’s heart, the news spread through Wardha like wildfire. People spoke in hushed tones of the doctor who could see inside the body with a machine. Whether it was the medicine or the profound “placebo effect” of such a grand investigation, my mother improved almost overnight. For months afterward, my father celebrated her recovery by having fresh fruits delivered from Nagpur, a sweet, seasonal testament to the day the “miracle of the machine” came to our home.