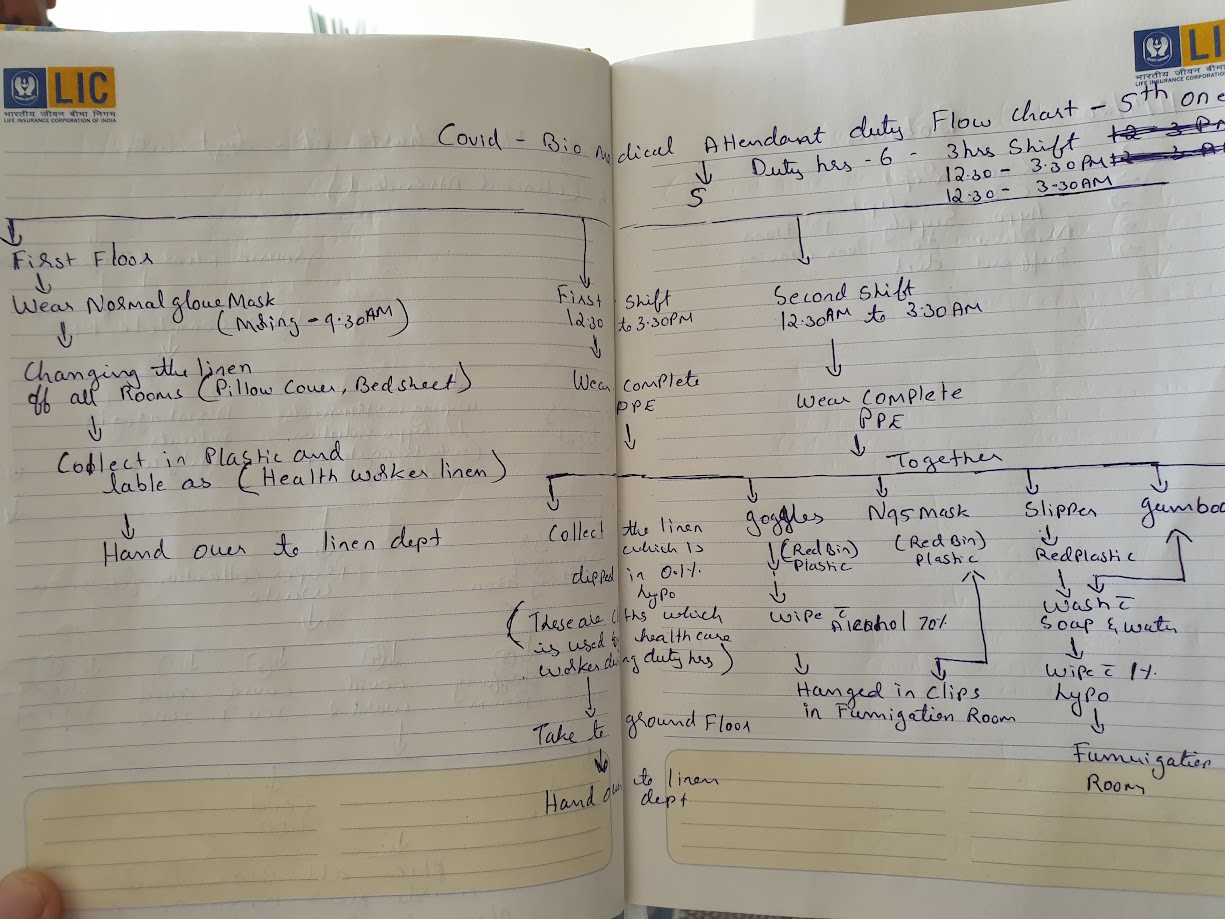

Meticulous protocols: A handwritten COVID-19 duty flow chart for hospital attendants, 2020.

In early April 2020, I stood in the central corridor of MGIMS and felt as though I were walking through a ghost town. For over a decade as Medical Superintendent, my walk through the hospital had been defined by a sensory overload: the smell of woodsmoke from the tea stalls, the cacophony of families gathered under the neem trees, and the constant, rhythmic hum of thousands of outpatients seeking healing. Now, that life had been surgically removed. The Outpatient Departments (OPDs) were eerily silent. The wards were empty. The lockdown had frozen the world outside, but for those of us inside the hospital walls, the silence was not peaceful; it was a deceptive, heavy pressure—the breath drawn before a long, sustained scream.

The Covid-19 pandemic arrived in Sevagram like a phantom. It didn’t just threaten our health; it threatened our institutional identity. We are a teaching hospital rooted in the Gandhian tradition—where the “touch” of the physician and the presence of the community are the very pillars of our mission. Suddenly, that which made us human made us vulnerable. The very acts of service we had practiced for fifty years—clasping a patient’s hand, sitting close to hear a whispered symptom, performing surgeries in the middle of the night—were transformed into potential acts of biological hazard. It was a civilizational disruption that felt personal.

***

The Anatomy Hall Summit

I realized that to lead through this, I needed to anchor our fear in structure. I convened an emergency meeting of all department heads in the Anatomy Lecture Hall. The choice of venue was accidental but became deeply symbolic. There we were, surrounded by the silent teachers of human structure—the skeletons and preserved specimens that represent the absolute certainty of medical science—while we tried to decipher a microscopic invader that was dismantled human certainty in real-time.

I looked at the faces of my colleagues—Subodh Gupta, Sumedh Jajoo, Dhiraj Bhandari, and the senior nursing supervisors. These were veterans who had managed chikungunya epidemic in 2007 and cholera outbreaks without flinching. Yet, in their eyes, I saw a reflection of my own uncertainty. The fear was visceral. It wasn’t just the professional fear of a rising mortality rate; it was the primal fear of the unknown. Would we have enough masks? Would the ventilators hold? And the question that haunted every staff member: If I go into that ward today, am I carrying death home to my children or my elderly parents tonight?

“Our fight will be driven by science,” I told the room, standing at the podium. I tried to project a voice that didn’t betray the knots in my stomach. “We will not be governed by anecdotes, we will not be governed by social media rumors, and we will not be governed by fear. We will build a fortress here, but it will be a fortress of evidence.”

***

The Architecture of Preparation: Repurposing the Old Hospital

Our first major step was a kind of logistical surgery. We knew the biggest danger was letting infected patients mix with the vulnerable. A standard hospital layout was a trap. So, my team proposed a tough plan: we would empty the entire old hospital building—the historic home of Surgery and Orthopedics—and turn it into a dedicated Covid Block.

It was a massive job. We had to move entire departments and relocate patients overnight. But the old building had a hidden advantage. Its layout of private rooms and separate wings was perfect for the strict routine of putting on and taking off PPE. We divided the space into a ‘Red Zone’ for patients and a ‘Green Zone’ for staff, creating a boundary that felt less like a hospital corridor and more like a front line

We also moved our screening outdoors. To keep the virus out of the building, we set up a makeshift open-air OPD in the long corridor between the Medicine department and the registration area. We realized the open air was actually our ally; natural ventilation was far safer than air conditioning, which could simply circulate the virus

***

The Hunt for “Gold Dust”

“In those early weeks, my desk wasn’t covered in files anymore. It was covered in lists of our new ‘gold’: N95 masks and PPE kits. I watched senior surgeons—men who had done thousands of operations—holding a simple face mask with the kind of deep respect usually saved for a delicate surgical tool.

“I recall the intense debates about using PPE wisely. Everyone—from technicians to sweepers—wanted to wear full ‘astronaut’ suits for every task. We had to balance their fear with the hard reality that supplies were running out everywhere. We had to teach our staff that science—not just layers of plastic—was their best protection.”

***

The Heartbreak of “No-Touch” Medicine

As Medical Superintendent, I was stuck in my office, far from the bedside, yet I felt every ripple of fear from the wards. I remember the young residents and nurses preparing for their first Covid shifts. Many were barely out of their teens. I saw the red marks of tight masks on their faces, and I saw them weeping quietly in the locker rooms as they pulled on their protective gear.

The heat in Wardha in April and May is legendary—it is a dry, suffocating furnace that regularly touches 45°C. Under those non-breathable plastic PPE suits, the temperature was even higher. Dehydration was immediate; exhaustion was absolute. Yet, the physical discomfort paled in comparison to the emotional toll of what we were being forced to practice: “No-touch medicine.”

For a doctor, touch is everything. But suddenly, we were forced to keep our distance. We listened to lungs through layers of plastic and spoke to gasping patients from behind glass. Later, to be honest, we stopped using our stethoscopes altogether. It felt cruel. We were caring for the most isolated people on earth, yet we were forbidden from offering the simple comfort of a hand on a shoulder. Fear was everywhere—in the canteen, in the labs, and in the silence of the ride home

And yet, I was far from the battlefield. I was sixty-four. Because of my heart condition, I was advised to stay away from the wards to save my own skin. I felt a deep, gnawing guilt. Was it right to ask young doctors to work without fear when I was safe in my office? It took time to make peace with this. Eventually, I realized my fight was not at the bedside, but at the desk—managing the chaos, enforcing science, and ensuring we used drugs rationally.

We were preparing for a war we couldn’t yet see. But in the Anatomy Hall, we made a pact. We decided that while we fought the virus, we also had to fight to keep our humanity. We would adapt, we would improvise, and we would struggle—but we would never abandon the discipline of care.