2.10

The Second year: Grinding Through

Bonding with Boyd; Sojourn with Satoskar

Boyd, bunk, and sudden silence

In medical college, Second MBBS is the middle overs of a Test match. The first-year terror has faded, and the final exams are still a distant cloud. You can breathe again. You can even pretend you are enjoying the subject.

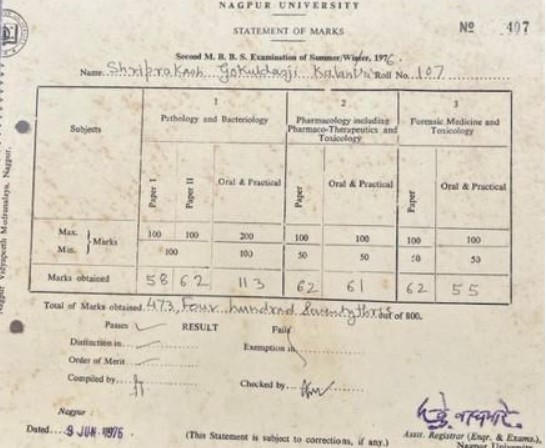

In the summer of 1976, we faced Pathology, Pharmacology, and Forensic Medicine. The scholars in our class walked around with thick copies of Goodman and Gilman, as if weight itself was a sign of intelligence. The rest of us found comfort in Satoskar. Dr. R.S. Satoskar wrote the way a good teacher speaks—simple, clear, and aimed at helping you pass without losing your mind.

Second MBBS, Nagpur University: not a topper, not a failure—just steady progress, one page at a time.

Pathology, however, was a romance.

We fell for William Boyd. Boyd was not a dry academic; he was a storyteller. He could describe a diseased gallbladder as if he were writing a scene from a novel—“graceful, fragile gossamer folds of the mucosa… loaded down by dense yellow opaque masses, much as a delicate birch tree might be weighed down by a load of snow.” He wrote that influenza could cross a continent as fast as an express train. He compared syphilis lesions to “the list of the ships in the Iliad.” We read him not only to learn pathology, but to feel the joy of language.

Forensic Medicine, alas, did not win our hearts. We studied it the way one swallows a bitter tablet—quickly, with water, and without asking for flavour. We did not yet know how often medicine and the law sit at the same bedside, arguing.

The Unlikely Anatomy Hero

Abhimanyu Kapgate came from a small village in Bhandara district. His English was hesitant, but his memory was a miracle. He knew Gray’s Anatomy better than most of us knew our own phone numbers. Ask him about the smallest muscle in the hand and he would recite origin, insertion, and nerve supply with the confidence of a man reading from scripture.

Cricket, however, was a foreign language.

Say “forward short leg” and Kapgate would stare as if you had asked him to name the moons of Jupiter.

One day, Narayan Dongre decided to test him.

We were all obsessed with syndromes then—Guillain-Barré, Cushing’s, Conn’s. Dongre asked Kapgate, with a perfectly straight face, about the “Greg Chappell and Andy Roberts Syndrome.” He followed it up with “Tony Greig Syndrome” and “Tony Gray Syndrome,” as if they were common conditions in Harrison.

Kapgate looked uncomfortable, but pride is a stubborn thing in hostel rooms. He did not admit ignorance. That evening, he went to the library and searched like a man possessed—turning pages, scanning indexes, hunting for the syndrome that did not exist.

He returned late, defeated.

Only then did we take pity and tell him the truth: these were cricketers, not diseases.

Kapgate was furious. He vowed revenge. But like many vows made between dinner and lights-out, it faded by morning, leaving behind only laughter—and a lesson in the cruelty of youthful humour.

A Silence We Never Understood

In the seventies, a shadow sometimes fell on medical colleges. The pressure was relentless. The hierarchy was rigid. The system had little patience for those who stumbled.

Suresh Chuttani was one of us. He came from a business family in Yavatmal. He looked fine—coping the way we all did, smiling when needed, studying when required.

Then, in the middle of the Second MBBS University examinations, the unthinkable happened.

Suresh took his own life in his room in Hostel No. 4.

The shock was absolute. He had written the theory paper the day before. How does a person sit in an exam hall one day and disappear the next? We searched for reasons, but found none that could hold the weight of what had happened.

Someone said he had been reading an Agatha Christie novel shortly before he died—Death Comes as the End. It is a small detail, but it has stayed with me for decades, like a line underlined in a book you never meant to remember.

In 1977, we lost Pramila Khapre too. She ended her life in the girls’ hostel. We never learnt why.

We moved on because we had to. Classes continued. Ward postings resumed. Exams arrived on schedule. But the corridors never felt quite the same.

Some absences do not leave quietly.

They echo.