My relationship with Sevagram did not begin with fanfare or a master plan. It began in the sticky heat of May 1982, when I arrived as a Senior Resident—not quite settled, not quite sure where I was headed.

Dr. Trivedi, the Medical Superintendent then, made it happen. He was a man of few words and quick decisions. He gave me a foothold and moved on. For a year, I worked in the wards, doing what young doctors do best—carry files, chase reports, and stay awake when the body begs for sleep.

Then in June 1983, a post appeared on the notice board: Lecturer in Medicine.

In those days, a government job was not a “career option.” It was security. It was respectability. It was the kind of thing families prayed for.

I applied.

***

The Interview Room

The interview room had an air-conditioner that hummed like a bored mosquito. It didn’t cool the room, but it made the silence feel official.

Across the table sat Dr. B.S. Chaubey.

To Maharashtra’s medical world, he was a titan—Dean of GMC Nagpur, brilliant, feared, and famously short-tempered. To me, he was something else: the man who had watched me closely during residency, the examiner who had seen my strengths and, more painfully, my hesitation.

He didn’t ask me the usual questions. No causes of splenomegaly. No management of DKA. He already knew what I knew.

He leaned back, looked at me for a long second, and asked the only question that mattered.

“So, Kalantri… you want to teach?”

“Yes, sir.”

“It is not the same as passing exams,” he said.

“I know, sir.”

That was it. A few more questions, a nod, and I was sent out.

When the result came, it was in my favour. On 1 July 1983, I signed the register as Lecturer in Medicine. I was twenty-six—barely older than the postgraduates I was supposed to guide.

The title changed overnight. The feeling didn’t. Inside, I still felt like a student who had wandered into the staff room.

***

The Morning I Nearly Failed Punctuality

If the interview tested my nerves, the first few months tested my timing.

Punctuality at MGIMS was not a good habit. It was a religion. And one Monday morning, I nearly became a sinner.

I had spent the weekend in Bhopal with my sister and returned by an overnight passenger train, confident I would make it comfortably for my 7 AM lecture to the 1979 batch.

Indian Railways had other plans.

The train rolled into Wardha East—today’s Sevagram station—at 6:35 AM.

I looked at my watch and felt my stomach drop. Twenty-five minutes. In that time I had to get home, wash up, change, and reach the college—six kilometres away.

I ran.

My mother met me at the door, alarmed by my face.

“Tea? Milk?” she asked.

“No time, Aai,” I said, already pulling off my travel shirt.

I splashed water on my face, threw on a clean khadi shirt and trousers, slipped into my sandals, and kicked my Priya to life. The scooter started on the first kick—one small mercy.

I was flying towards Sevagram when I saw it.

The railway crossing.

Gate down. Red light blinking. A long passenger train crawling through like it had all the time in the world.

I braked hard. Dust rose. My lecture began in ten minutes.

And then I saw a friend on the other side, waiting to go into Wardha. We locked eyes through the iron bars. He understood immediately.

“Swap?” I shouted.

“Swap!” he shouted back.

I left my Priya there, jumped the tracks like a thief, and ran across. His scooter was an old Lambretta—battered, noisy, and stubborn.

It groaned. It smoked. But it moved.

I drove that Lambretta as if my job depended on it. Maybe it did. The speedometer needle shook its way towards eighty. There were no helmets in those days, only youth and poor judgement.

I reached the college, parked, and sprinted to the lecture hall.

As I entered, the clock clicked to 7:00 AM.

The students looked up, mildly surprised, as if I had been dropped from the ceiling. I stood at the podium, caught my breath, picked up the chalk, and wrote the topic on the blackboard.

Only then did my heart slow down.

I had beaten the clock—by a whisker.

***

The Department of “P”s

The Department of Medicine in the early 1980s was not just a workplace. It was a small world with its own rules, its own hierarchy—and its own shorthand.

We called it the department of “P”s.

There was KP—Dr. Kamal Pervez.

There was JP—Dr. J.P. Sharma.

And now there was SP—me.

We were the junior lot. The foot soldiers. The ones who lived in the wards and carried the department on our backs, one admission at a time.

Above us sat the two peaks of the place: OP and AP.

Dr. O.P. Gupta was the sun around which everything revolved. He wore khadi like armour and arrived at 8:00 AM sharp. If you came at 8:05, you didn’t need a watch to know you were late. His eyebrow was enough.

He had an old-fashioned memory. He didn’t need the file to know the patient. He remembered the pulse rate from yesterday and the potassium from the day before.

Dr. A.P. Jain was the counterweight—precise, minimalist, and dangerously sharp. He moved through the ward like a detective, looking for what everyone else had missed: a soft murmur, a faint rash, a line in the history that didn’t fit.

And then there was Dr. Ulhas Jajoo—the conscience of the department. He reminded us, again and again, that illness did not come alone. It came with poverty, fear, and the cost of missing a day’s wage.

Together, they ran the department like a family—loving, demanding, and slightly terrifying.

***

The Tribunal

Every morning began with a ritual that taught us more than any textbook ever did.

ECG correction.

We gathered in the old hospital building—the former Birla guest house. The wooden floors creaked. The walls peeled. The place smelled of phenyl and old paper.

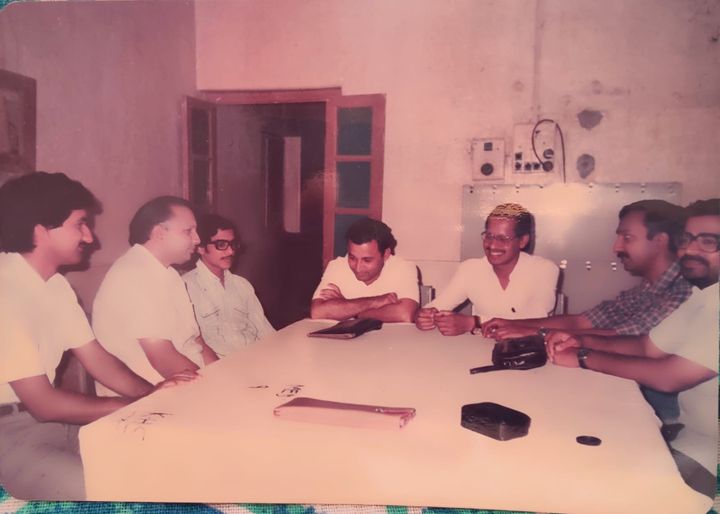

In a small room, the three of them sat together—Gupta, Jain, and Jajoo—like a bench of judges.

A resident would step forward holding a long strip of pink ECG paper, as if it were a confession.

“Read it,” Dr. Gupta would say.

The resident would begin, cautiously. “Sinus rhythm… rate 78…”

Dr. Jain would interrupt softly. “Look at V6 again. Is that a U wave or a P wave?”

And Dr. Jajoo would bring us back to earth. “You are reading a paper. Where is the patient in your thinking?”

There were no digital machines. No automated interpretations. No troponins. No quick CT scans to rescue you from doubt.

We had only our eyes, our ears, our stethoscope—and that strip of paper.

We dreaded that room some mornings. We also grew up in it.

Because in Sevagram, we learnt something simple and lasting: technology helps, but it doesn’t think. The doctor has to do that part.

And in the Department of “P”s, there was no escape from thinking.