In the Marwari tradition, the word “Bhaiji” is more than a name; it is an anchor. It conveys a specific blend of reverence, respect, and patriarchal authority. For my father, who was born on June 19, 1916, in the tiny village of Taroda, the journey to becoming “Bhaiji” was not a path laid with silver spoons, but one carved out of the hard rock of survival. To understand the man he became, one must first look at the silence from which he emerged.

He was an orphan of the shadows. By the age of five, an infectious disease had claimed both his parents, leaving him with no photographs, no yellowed letters, and no stories passed down through generations. He grew up in abject penury, an experience that would have broken a lesser spirit, but in him, it forged a steel-trap mind and a relentless drive for self-reliance. He rarely spoke of the hardships of those early years—the winter mornings waking at 4:00 AM to bathe in a cold river or the ten-hour days tending livestock. He carried those scars silently, translating his pain into a staggering work ethic that would eventually define our family’s trajectory.

The Acid Test at Gandhi Chowk

Fate often wears the mask of a stranger. For my father, that stranger was Shri Chiranjilalji Badjate, a Munim for the Bajaj Group. In 1932, Chiranjilalji spotted a sixteen-year-old boy in Taroda chasing after grazing cattle and saw something in the boy’s eyes—a spark of intelligence that didn’t belong in the dust of a pasture. He brought him to Wardha to meet Jamnalalji Bajaj, the man Gandhi regarded as his fifth son.

The interview was not a test of academic merit, but of ego. Jamnalalji looked at the boy and asked: “Will you willingly clean the toilet?” My father didn’t hesitate. He said yes. This was the “acid test” of the Bajaj Group—a search for a man who was a Peer, Bawarchi, Bhishti, Khar (Saint, Cook, Water-bearer, and Donkey). By saying yes to the most menial of tasks, my father opened the door to a forty-six-year career that would see him rise from a jack-of-all-trades earning eleven rupees a month to the Secretary of the Jamnalal Bajaj Seva Trust.

The Devotion to Numbers

If my father had a superpower, it was his relationship with numbers. He possessed a staggering devotion to the “Parta”—the centuries-old traditional Marwari system of financial monitoring. To him, an account book was not just a ledger; it was a moral document. He had a photographic memory for figures and an uncanny ability to spot a manipulated number from across a room. Under the mentorship of Chiranjilalji, he learned the foundational adage of his professional life: “Whatever happens, the accounts must be in order.”

I remember him in his office at Gandhi Chowk, surrounded by the heavy ledgers that were the essence of his world. He was a stickler for detail, often checking his work multiple times to ensure perfection. This wasn’t mere bureaucracy; it was a form of integrity. In a world of shifting allegiances, numbers were the only things that didn’t lie. He managed nearly a hundred acres of Bajaj land and oversaw the Shri Laxminarayan Devasthan Trust with the same meticulous precision he applied to our own household. He taught me that whether you are managing a charitable trust or a hospital budget, precision is a form of respect.

The Radical Reformer

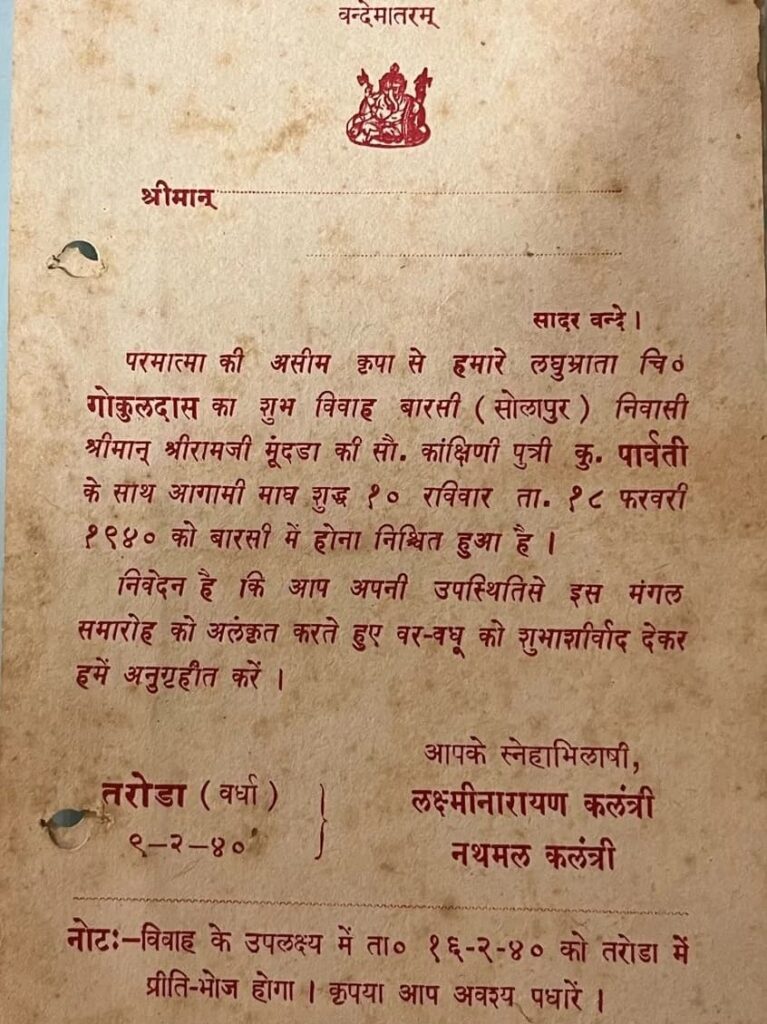

Despite his traditional roots, my father was a man far ahead of his time. His exposure to the Gandhian circles of Wardha and the influence of Jamnalalji and Jankidevi Bajaj turned him into a quiet revolutionary. Nowhere was this more evident than in his own marriage to my mother, Parvati, in 1940.

In an era where the ghoonghat (veil) was an iron rule of Marwari society, my father set a shocking condition for the wedding. “I insist that the bride does not wear a ghoonghat throughout the ceremony,” he declared. To my maternal grandparents in Barshi, 500 miles away, this was unfathomable. They worried about how a girl from a traditional background would adjust to a “dark-complexioned orphan” who demanded she show her face to the world. Yet, my father prevailed. It was the first wedding in that community where the bride remained unveiled, a bold act of defiance inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s call for women to discard the parda. He believed in the dignity of the individual over the comfort of tradition.

The Architecture of a Home

My father’s sense of precision extended to the very walls we lived in. In 1967, when we moved into our current residence, he didn’t just buy a house; he envisioned a transformation. He sought out the renowned architect Mr. Sheodanmal to redesign our home. When the architect spent only thirty minutes inspecting the premises, my mother was disappointed, but my father knew better. He understood that a master eye doesn’t need hours to see the truth.

He, along with my brother Om, dedicated themselves to the construction of “Jaishree Bhavan.” My father’s eye for detail was relentless. He personally supervised the “curing” of the walls and hired a sixteen-year-old boy to lay the floor tiles with such meticulous alignment that today, five decades later, they remain as pristine as the day they were laid. He believed that if you build something, you build it to outlast you. Our home was a physical manifestation of his philosophy: solid, precise, and built on a foundation of hard work.

A Fiery Temper and a Golden Heart

To present Bhaiji as a saint would be to do a disservice to the complexity of his character. He was a man of fiery temper and little patience for opposing views. He lived by a binary code: “either you are with me or against me.” He was arrogant about his convictions, and his anger could be formidable. Yet, this same man was capable of extraordinary, quiet kindness.

There is the story of Mr. Tapdiyaji, a young man who was turned away from a professional office because he wasn’t wearing “formal” clothes. When my father heard of this humiliation, he didn’t just offer sympathy. He provided the funds for Tapdiyaji to buy a suit, lent him the family car, and personally vouched for him. That one act changed the course of Tapdiyaji’s life. For decades after, until my father’s death, Tapdiyaji would visit our home every Dussehra to touch my father’s feet. My father didn’t seek gratitude; he sought to correct an injustice.

The Final Departure

My father lived as he died—with a quiet, unsentimental fearlessness. He passed away on December 21, 1986, at the age of seventy. He didn’t spend a single day in bed; he didn’t endure the slow erosion of a prolonged illness. He faced death quickly, without regret, much like he faced the “acid test” of his youth.

We took his mortal remains to Haridwar, accompanied by his guide and philosopher, Radhakrishnaji Bajaj. As we immersed his ashes in the Ganges, I realized that while the man was gone, the “Bhaiji” remained. His legacy was not just the property he built or the accounts he balanced, but the resilience he instilled in us. He was a man who rose from nothing, defied the norms of his time, and taught his children that grit, integrity, and a devotion to truth—whether in numbers or in life—were the only things that truly mattered.